Cem Kaya’s fantastic documentary Remake, Remix, Rip-Off screens at FrightFest this weekend. It’s a long-awaited delve into the wild, wild world of the Turkish Fantastic Cinema (AKA Turkish Pop Cinema, AKA Turkish Remakesploitation) and it doesn’t disappoint – long-time fans, casual observers and complete novices alike should enjoy Cem’s film. I’ve written about it a little before (see here and here), partly in response to how thin and misguided most of the coverage of these films seemed to be, and subsequently found those articles to be, consistently and by some margin, the most popular on this blog. At the time, I found sources available for research very spare, so this documentary was really kind of a feast for me – as it will be for you! I saw Remake, Remix, Rip-Off at Edinburgh International Film Festival back in June, and shortly thereafter Cem very graciously offered his time for what turned out to be a very long chat.

NB, if you’re looking for a first-time primer on Turkish fantastic cinema, try here, this BBC article, or Joe Zadeh’s recent piece in The Guardian, featuring Cem and his film. OK, sitting comfortably? Let’s do it.

SW: How did you first come across these films?

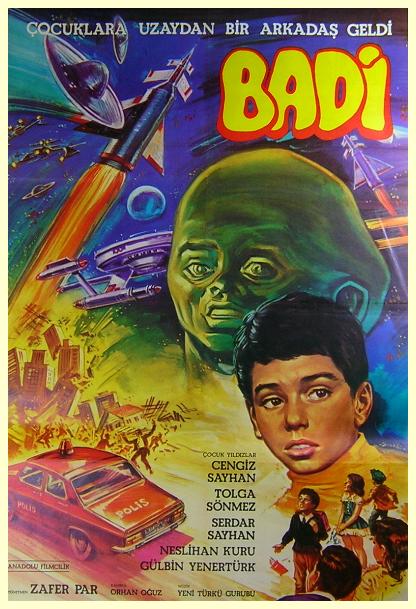

CK: I remembered the films I had seen as a kid [in Germany], because my stepfather owned a videoshop and I grew up with these films. When my stepfather came home, he always had two tapes with him, when he came home from work. In the evenings, two films came and these two films were watched. And we had a stock of films at our place, so when we got bored, when German television was too boring, we watched a Cüneyt Arkın/Çetin İnanç film. Not knowing that these were important films. For us, it was just entertainment. And when this was over, I did other stuff and I had no interest in Turkish films at all. I also lost my Turkish. I had to re-learn Turkish in the 2000s. I was always thinking whether, for instance, the action scenes with the Matchbox cars [in lieu of stunt cars], whether I’d really seen them, or this was something out of my imagination. Because I had seen them as a kid and I also saw, as a kid, that they were Matchbox cars. I just didn’t care. I just liked it. But then later I was telling people about these films, but the video stores had closed in the 90s because of satellite technology, so people could watch Turkish television, so the video stores, they just closed and all the films in Germany were destroyed.

This is the golden video tapes.

Yeah, the gold one was a special edition. For the video company owners, and the audience, the director wasn’t important, unless it was Yılmaz Güney. But for them, it was important who was playing in it. Therefore, for us, it was always a Cüneyt Arkın film. And Çetin İnanç I just got to know when I did research on the films. In 2003, when I then began, I was saying, “Hey, do you remember these funny movies, these Turkish movies, how absolutely exaggerated they were and the excess in these movies and all these special effects? I want to do something about these movies.” That was the approach. It was maybe also a very naïve approach. When I then got into the research, getting the films and watching them again – I found many films in German libraries. In one library, in Stuttgart, there was a corner full with Turkish films. So I got these and I got into Turkish film history and I watched all these films, again, again, again, again. And then I read some academic research, because there were brilliant PhDs written about these films too, then I just broadened the topic and then I went into this serious business. Then I made a film in 2005, Do Not Listen!, which is a juxtaposition between The Exorcist and its Turkish remake, Seytan. It’s a 15-minute found footage film.

Remake, Remix, Rip-Off is really the first telling of this story. Did you feel that sense of responsibility when you were making it?

No. It took me 12 years to do research on the entire topic. When I began, I made a diploma thesis and a Masters thesis on Turkish films and especially on remakes in Turkish films. It had the same name – Remake, Remix, Rip-Off. I did so much research and there’s so much, let’s say, knowledge about these films and about the background of film history in Turkey and how you should approach the evaluation of these films to be able to understand them. And if you then go into Turkish history, then you really have to go back into 16th-17th century and look how the Ottoman Empire opened to the Western societies. Because they were in a decline, they wanted to know how Europe was so strong, and so [they said], “Let’s see what they’re offering culturally,” and technically, because it was all about weapons in the end. So what they did was they opened themselves to Europe. A lot of painters, artists and writers came to the Ottoman palaces and they were deeply influenced by these Western cultures that opened to them. But they had to translate the Western literature and, during this translation, transformations began. They had to somehow make it available for their own readers. And doing this, all this appropriation began.

When American movies or foreign movies got dubbed, it continued by dubbing them differently than the original films, or by putting belly dance scenes or mosque scenes into the films to make them look as if they were shot in Turkey. And all these strategies in the end lead to Dünyayı Kurtaran Adam [AKA The Man Who Saves The World, Çetin İnanç, 1982], which took from Star Wars. So if you know the historical background and you trace it back, and you work on the sociological level with the topic, then – now I come back to your question, whether I felt responsible to tell stories – sure, I would like to tell more about it than, “How funny, the Turks did that, and they did it under these circumstances, if they had money or there wasn’t censorship, they would have done better,” which my film is basically saying. There are so many other things I would like to tell, but I just can’t in an entertaining documentary – it’s not entertaining anymore. I then decided to put all the sociological and historical aspects away. I just put into a frame that’s really general, because I thought if somebody is interested in it, they can read it on Wikipedia, later. And so I concentrated on the filmmakers themselves because there are enough stories in the movie that pose questions about today, all these patent and copyright issues we have. Myself, as a documentary filmmaker, I’m not allowed to use all these clips if I can’t clear them. So I was sitting there with lawyers and with copyright people and I had to clear The Godfather, and I had to clear the Star Wars footage.

Did you have any particular problems, other than just the hassle of the whole thing? Anything that you couldn’t use?

No, I couldn’t use some stuff that I couldn’t clear in Turkey, because I just did not find the copyright holder of some films. But my film is produced by ZDF, which is German television and by UFA, which is one of the biggest film production companies in Germany. A lot of people in Germany asked me, “Why did you produce the film with these guys?” All the little production companies said, “We can’t make it, because it’s just too many copyright issues.” You need a budget to do a film like this and you need an organisation who can just deal with it and who have maybe also the right connections, which the UFA has. You can also say it’s fair use, but no television channel is going to give you money if you just say, “Yeah, we think it’s fair use.”

Watching it, some of the footage looks better than I’ve ever seen it before. Did you have to source original prints, or how did you find the footage?

In the 2000s, films on the internet weren’t so common and there wasn’t much about Turkish film, so I went to Istanbul. I went back and forth all the time, between Berlin and Istanbul, and I went to pirates and they made copies for me. There’s a scene that always was collecting Turkish films. Before digital technology, it was VHS and Turkish television showed a bunch of films, but for the really hardcore ones I had to contact some people like Metin Demirhan, who’s in the documentary, who wrote the book Fantastic Turkish Cinema [Fantastik Türk Sineması, with Giovanni Scognamillo]. He gave me VHS tapes and then I was in secondhand stores and doing deals with video pirates, where I take 100 or 200 films from them, and it was cheaper for me. Then there’s the Mimar Sinan [Fine Arts] University. They have an archive but you can’t get films out. You have to be there and watch the films at their monitor, so I was sitting for hours. And the more the internet developed, I had more access to the films and there were some platforms where you could trade films. And then one friend who was an archivist I could ask him for films that were hard to find and so over the years I got myself my own archive.

People are used to seeing this kind of Turkish cinema on really terrible, shitty YouTube clips, and that really contributes to how they think of it. They think it’s bad quality and poorly made and some of the poor subtitling even, which, we’re lucky to have the subtitling we did have, but because it was historically not that great, it contributes to the comedic effect.

As you say, the bad reception of the films is because of the bad copies too. All these films were bad quality, mostly in bad shape and so I pre-edited the film with these films and after the editing was done, I went to the production companies – and I had contacted them before too because I had to clear the rights in advance – because I couldn’t just begin with the film and put so much money into it and then go there and ask whether the rights could be cleared. I went to all the production companies that I knew in Istanbul and told them, “Look, I’m going to make a film using footage from your pool and ZDF and my production company, they want guarantees that we can clear the rights later.” So I got papers from them in advance, to show to the institutions here that it’s possible to clear rights in Turkey, that it’s not so difficult. And so when the editing was finished, I went to the production companies and then I demanded clean copies. But the clean copies that they were able to give me were Beta SP or DigiBeta copies – nobody gave me a 35mm copy. To be able to sell the films to private television, they had made these beta copies of the films and most of those were also in bad shape, because they were recorded in the ‘90s. So I had to deal with the mostly bad footage that I got and then, because I come from post-production, I did treatment on the pictures again. I could have shown it in a bad shape – I watched it in a bad shape. When I was a kid, I watched it from VHS and it was just bad. But I wanted to create the feeling that somebody in Turkey in the ‘60s or ‘70s would have had when he’s gone to the cinemas. Because in the cinemas, the quality was brilliant.

Do you think there’s any chance that whole films will get that treatment?

Classics are being restored. The problem with restoring, digitally, is that they over-restore them. They’re too clean, because they want to make them good for HD TV, because they’re selling them to private television. This is the big problem – restoring them properly, keeping some of the dirt, not to over-clean them. Also, most of the films are shot 4:3 or 5:4 and now to make it suitable for television, so they just cut them, they make them bigger, the top and bottom are cut off. It’s letterboxed, but there’s parts missing. Generations later, when they are watching the Turkish classics, they’re just going to watch these versions and they are censored, too, because there’s television censorship regarding alcohol and cigarettes. They were censored before and then they get censored for television. So we always have these over-restored, totally clean, letterboxed and double- and triple-censored films. This is not the way it should be, but putting 20,000 euros into the restoration means you have to get 200,000 euros for selling it to television. So you need a film preservation fund or funding to be able to restore them properly.

Those films are maybe not so well-regarded in the West because they’re so specific to Turkey.

Yeah, exactly. Maybe. There are some that went to festivals too, but the western audiences always liked the kind of films where people suffer in, because when they look into the third world, they have this western centralised view and they always need films that are dealing with human rights issues.

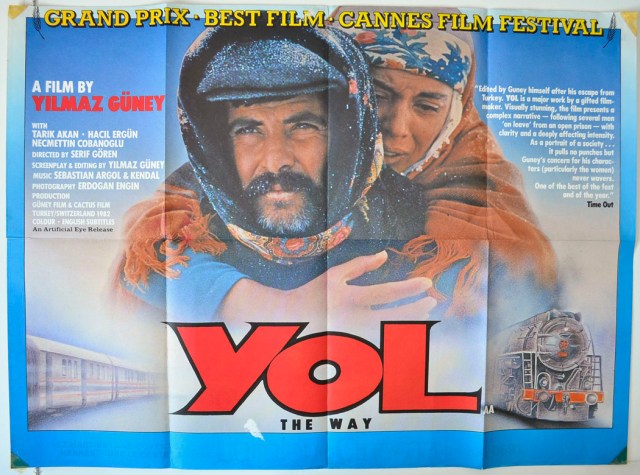

Yes, like Yılmaz Güney’s films. So you have the so-called trash on one end, and the Güneys on the other.

Güney is a really nice example because Güney himself was coming from the action and trash genre and he was one of the biggest action stars in Turkey, but in the cheapest films you can imagine.

Çetin İnanç talks about him in your film. They knew each other.

Yes, they knew each other because Çetin İnanç worked as a director’s assistant or production assistant on many of Güney’s films. In the Yeşilçam [literally “Green Pine”, equivalent to “Hollywood” in American cinema] era, auteur film or arthouse film and trash film or mainstream film, whatever you may call it, wasn’t separated like it is today, because it was the same people who did both. And I think this is the interesting part in Yeşilçam, that it was an industry and sometimes the industry allowed you as a director to make an arthouse film. Imagine it like this – somebody comes to you, a producer from the distribution area comes and says, “I want to have 12 films from you,” and he says, “I want to have three films that are like these American movies but I want to have these Turkish stars. And then I want to have three comedies with this or that comedian. And then I want to have one religious film because Ramadan is approaching.” And then he says, “And then there’s one film, you can do whatever you want.” This one film, you can do whatever you want, is a door for possibilities. Because then if someone does something that hits the audiences, then there is another door.

So next time they say, “Can I have three of those kind of films?”

Exactly. Because, all the formulas they have, people get bored of them. A formula, a story like Wuthering Heights, you can tell it maybe 10-12 years and then even the dumbest audience will say, “Come on, we’ve seen that film.” So then you have to change it or do something else and therefore, much more than the TV industry today, they had the freedom to also do some films they wanted. And then you see, when you watch some Turkish classic movies, “Hey, it’s the same scriptwriter, it’s the same director, it’s the same actors,” but the movie is a different movie because they then do what they want to. But also in the frame of their talents and the technical possibilities. But then you see in one of these “good” films, like Yılmaz Güney’s marvellous film from 1972 [Ağıt], you had also Italo-Western soundtracks in the film, because the strategy is the same, it’s how the industry works. They just don’t see any copyright issues because the soundtrack is not registered in Turkey. They don’t even import it. They go to Italy, buy the soundtrack, come back, so it’s not published in Turkey. For not being published in Turkey, it’s not protected in Turkey.

So they can feel free to use it as many times as possible.

Yeah, exactly. Because the films go through censorship twice. There’s the police, the military, the ministry of culture and a bunch of people watching these movies before they get the stamp to be allowed to be shown in Turkish cinemas. So, from the point of view of the filmmakers, if there’s nobody saying, “But, stop, here you’ve used the James Bond soundtrack, this is not allowed,” then, for them, it’s just legal. Everybody says, “How could they? How dare they? They were stealing,” No, they’re not stealing. They’re just using what was in the public domain.

Did you speak to everyone you wanted to?

No, because many people had died. There was one, if you ask me, very important director called Yılmaz Duru, and Yılmaz Duru is also a visionary guy and it’s amazing the films he does. They seem to be regular, normal films and then when you get into them, there is such a madness in them, and after 30 minutes, the film changes and becomes a different film, the script changes and all of a sudden you’re in something different and after one hour, he changes again the script and you’re in another tale. The guy is just… I think this guy isn’t where he deserves to be in Turkish cinema history and I would like to do more research on him. And he’s not even in my film! He’s just in the thanks. He’s the last name in my list of thank yous. He died. I was just too blind and too dumb while he was living, because I was in Turkey while he was living, just to get the idea, or I just hadn’t seen his film yet, to get an interview with this guy. And when I was enlightened, he had died, unfortunately. So I went there and filmed his funeral. So half of the time I was there, I was filming funerals.

Çetin İnanç’s last line, saying that he wants to speak now because he’ll be dead soon, was that the underlying impetus for all these guys to speak to you?

Yeah, I think so. The most important reason we got Çetin İnanç to speak is that we knew somebody who was very close to him, the person that made the book about him. It’s very well written because she is a Turkish journalist and she is his cousin. It’s called The Jet Director [Jet Rejisör Çetin İnanç]. But nobody before had a recorded interview with Çetin İnanç, because he’s just hiding. When you call him, he says, “Oh, he is not here.” He doesn’t reveal his identity. He just doesn’t want to because he knows that people approach him to make fun of his films. In the 90s, when college students had discovered films like The Man Who Saved The World for the first time, they had screenings at the Boğaziçi University. At one of these screenings, for Malkoçoğlu Kara Korsan (Süreyya Duru, Remzi Jöntürk, 1968), they had a sign saying “The Cinema Club of Boğaziçi University presents with shame…” This is what I’m talking about. Because, in Turkey, all the films had “proudly presents…” And Cüneyt Arkın was outraged, “How could you do this?” So the students were thinking, “Ha-ha, funny movie,” but this was just inappropriate and maybe it tells you something about the reception of these films. They said, “We Turks, we also had an Ed Wood, and here is the film, and it’s funny, funny, funny…” It’s just the funny aspect they’re after. I think this is a big problem.

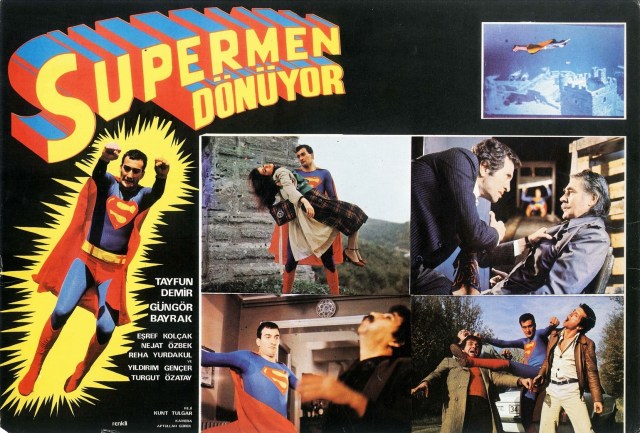

It’s the same problem internationally. It’s kind of a double-edge sword because that kind of interest spreads the word about them. “Oh, my god, there’s this crazy film that uses footage of Star Wars,” or “There’s this version of Superman that uses James Bond music.” And that makes people interested but unless there’s a follow-through from it, it’s a real disservice.

Everyone talks about the wooden sword [in Dünyayı Kurtaran Adam]. Cüneyt Arkın said once in an interview, “There were times when we didn’t even have that. We did it with our bare hands.” And that’s the spirit I’m talking about. And this had a lot to do with politics and with censorship and also money, the possibilities of making film. And also with this unjust battle against the Americans, because, imagine, back then in 1982, 83, shortly after the military coup in Turkey, all the cinemas were flooded with the American movies all of a sudden. So what chance had Yeşilçam cinema to fight against it? They just made the remakes, or they stole, as in the case of The Man Who Saves The World, they stole it literally.

They stole the Star Wars print.

Yes, and imagine the people who watched Star Wars back then in Turkey and Istanbul – they watched it with these scenes missing! So the context is important. He’s stealing from the cultural imperialists, in effect, and taking from the rich and showing to his poor audience. This is really important to understand, because the very same year, in 1982, Yılmaz Güney gets the big prize at the Cannes Film Festival for his film Yol, The Road, which is a film against the coup, against the American imperialist, against Turkish traditions, against all that is wrong in Turkey. And then the auteur cinema lovers applaud him and they give him, together with Costa-Gravas, the prize. In the very same year, the film that is considered the best film in Turkish film history, Yol – for years it was the Turkish film and when people talked about Turkish cinema, they were talking about Yol – and then the movie which represents the worst of Turkish film, The Man Who Saves The World, which is on the list of the worst films ever made, they were made in the same year and the directors were friends. I’ll tell you another story and you’ll understand where I’m leading this.

There is a film called Hudutların Kanunu by [Ömer] Lütfi Akad. Lütfi Akad, one of the greatest Turkish film directors ever. It is one of the films in which Yılmaz Güney appears as a serious actor, and not as an action actor. During this film, Yılmaz Güney gets arrested again, for some of his writings, I think. They were in Adanda in the south of Turkey where Yılmaz Güney had his base, and they had mules in Adana, white mules that they had filmed. Çetin İnanç was a production assistant on this movie and when Yılmaz Güney got arrested in Adana, they had to go back to Istanbul, but there were no mules in Istanbul, they just couldn’t find mules. So, what did they do? Again, it was the vision of Çetin İnanç. He said, “We take donkeys, we paint them white and from far away, we film them as if they were mules.” So painting the donkeys white and filming them from afar is exactly the same thing as taking Star Wars footage and putting it in your film. It’s the same strategy. You see where it comes from. It’s, “How do I get my film completed?”

So Yılmaz Güney does the best film ever, Çetin İnanç does the worst film and it’s done in the same year. One is an important film because it points to the critical things in Turkish society, the other one is a science fiction film, but the subversive thing in the other one is that it steals from the cultural imperialists. These things, I can’t tell in my film. I don’t know whether people sense it, or whether what is there is enough, but I would like to put these things in a book maybe or a blog or whatever, to make them available for people, because these thoughts matter. I spoke to around 100 people and each interview was at least 1.5 hours. These interviews are still here, so I have to do something with those too. There’s so much information and valuable things and it’s oral history. There are no other people, neither in Turkey nor abroad, because they don’t know, who evaluate Turkish cinema in way I think it should be evaluated.

How do you feel about the term “Remakesploitation”?

I don’t know. I think the term is better than “Turksploitation”!

I think maybe “Fantastic Cinema” is more appropriate.

Me too.

Sean Welsh

Read part two of my interview with Cem Kaya here!

After screening at FrightFest, Remake, Remix, Rip-Off is on its way to Texas for Fantastic Fest in October, where they’ve built a strand of Turkish Fantastic Cinema around it. After that, a cinema release in Germany and Turkey, a German TV screening and eventually VOD and DVD.

Pingback: INTERVIEW: Cem Kaya (Director of Remake, Remix, Rip-Off) pt II | Physical Impossibility

Pingback: Interview with director Cem Kaya in Physical Impossibilitiy by Sean Welsh | Remake Remix Rip-Off News

Pingback: Remake Remix Rip-Off Trailer – Prohdmoviez.com

Pingback: Motör aka Remake Remix Rip-Off – TubeNine.com

Pingback: Remake Remix Rip-Off Trailer - Video Toronto Community

Pingback: Motör aka Remake Remix Rip-Off – Fragman fragman | 2 video izle

Pingback: Remake Remix Rip-Off Trailer – Profit Power economics

Pingback: Motör aka Remake Remix Rip-Off – Fragman – Profit Power economics