“Especially in America, I think people are born into tribes. And I wanted to make a movie about two different tribes that end up colliding and then the reverberation of a violent episode. I wanted to do something about how you can’t get away from history. I wanted to make a film about that, but also deeply personal, about becoming a father and passing things on.”

Derek Cianfrance1

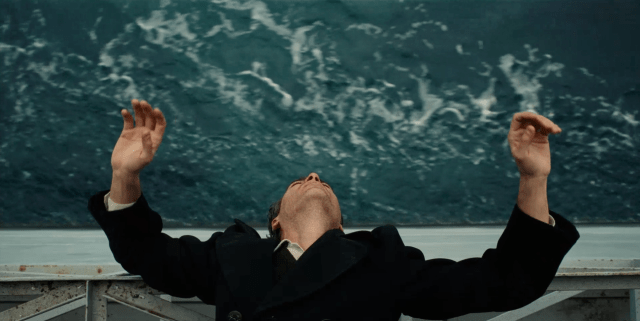

Derek Cianfrance’s ambitious third feature, after the little-seen Brother Tied (1998) and his breakthrough film Blue Valentine (2010), is a triptych, concerned with personal responsibility, family and, above all, legacy. Where Brother Tied was concerned with siblings and Blue Valentine husbands and wives, The Place Beyond The Pines (Dir. Derek Cianfrance, 2013) is about fathers and sons. All three films are intensely personal and chiefly preoccupied with the psyche of the modern American male. Where the director’s latest differs is in its grand scope – quasi-epic and generation-spanning – which seems to invite similarly grand analysis, while attempting to sustain the same specificity and intimacy of his previous films.

Brother Tied, made when Cianfrance was 23, remains unreleased, expensive music rights barring it from an audience wider than a largely appreciative film festival circuit. Telling the story of a man torn between allegiance to his brother and a newfound friend, it’s black and white, technically precocious and arguably overambitious. 15 years later, the director has been frank in his own analysis, saying, “It was all about my tricks as a filmmaker… It was content illuminating form instead of what I’ve learned since then, what I learned sitting on the bench, sitting in the cinematic desert, was that form is there to serve content.”2 Lesson learned, Cianfrance’s next effort arrived 12 years and 66 script drafts later.

Cianfrance’s devotion to authenticity – he ensured his The Place Beyond The Pines stars were surrounded “with the real people that made up the fabric of Schenectady, with real police officers, with real judges, with real bank tellers who had been robbed before”3 – is consistent with the approach he established with Blue Valentine. The production was famously method – the film’s leads, Ryan Gosling and Michelle Williams, lived together in preparation for their roles as husband and wife. Cianfrance had them live on a budget equivalent to their characters’, take family portraits and stage arguments. As with The Place Beyond The Pines, the director encouraged his actors to build their own characters, collaborate on their wardrobe choices and redraft or abandon the script entirely. Much of the film’s dialogue was improvised, with some scenes entirely unscripted. The focus was tight upon the couple in question and the result was almost brutally intimate and punishingly unromantic.

Cianfrance has discussed his various inspirations for the form of The Place Beyond The Pines – notably Abel Gance’s Napoleon (1927), a narrative triptych itself and hugely technically ambitious, and Psycho (Dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 1960) for its mid-film switch between protagonists. Napoleon is an historical epic while Psycho hinges around the shock death of the apparent lead character and both were formal trailblazers. Cianfrance’s challenge in making The Place Beyond The Pines was to take the intimacy, tight focus and emotional honesty of Blue Valentine and marry it to a more formal, even artificial structure. He worked on 37 drafts of the script with two other writers over several years before letting his actors loose on it.

The title, courtesy of co-writer Ben Coccio, is a loose translation of the name of the film’s locale, Schenectady, a word of Mohawk derivation, roughly meaning ‘beyond the pine plains’ – as the area was defined from the perspective of nearby Albany. The choice of title subtly frames the narrative in the context of America’s bloody history and gives deeper resonance to the interior conflicts of the film’s protagonists. Cianfrance has said, “Thinking about how brutal our ancestors had to be, the brutality and ruthlessness with which this country was founded on, I think about now – we’re very civilised and domesticated, but I don’t think that ever goes away.”4 The director, who was shortly to become a father for the second time as he began working on the script, saw a correlation with a sense of the inescapable legacy passed from parents to children.

Cianfrance’s formal conceit allows him to fully realise his theme of legacy, and particularly paternal responsibility. The two contrasting ‘tribes’ – of Luke Glanton (Ryan Gosling) on one side and Avery Cross (Bradley Cooper) on the other, represent two sides of the same coin. One struggles with paternal absence, the other with presence – Luke wants to be there for his son as his father was not for him, while Avery struggles to escape his father’s long shadow. Each is defined by their desire to define themselves in opposition to their fathers, and their tragedy is that their efforts only perpetuate the cycle they wish to break, leaving it to the next generation to begin the struggle anew.

Cianfrance’s artifice in tying together the two families with Luke’s early demise at the hands of Avery and Luke’s final decisive act, requesting his son not be told about him, sets the stage for the film’s resolution. 15 years into the future, Luke and Avery’s sons are grown and dealing with familiar issues in different ways – Luke’s son Jason (Dane DeHaan) has a caring father figure in Kofi (Mahershalalhashbaz Ali), but somehow feels the absence of his biological father. Avery’s son AJ (Emory Cohen) seeks to define himself in opposition to his distant father, now running for New York State Attorney General.

Cianfrance’s conclusion is formally apposite, with both Jason and AJ seemingly coming to terms with their respective legacies in positive ways – Jason eschewing bloody revenge for his father’s death and the previously thuggish AJ standing besuited by his father at an event. Truthfully, though, the ending is not uncomplicated. The transformed AJ seems uncomfortable joining his still-distant father. Jason meanwhile hits the road on a motorbike, having been sold a romanticised vision of his father by Luke’s erstwhile partner-in-crime. How either will fare is an open question, though Cianfrance implies it’s in the nature of these things to evolve rather than resolve.

Sean Welsh, November 2012

This article was originally commissioned as a programme note by GFT.

Footnotes

1. Derek Cianfrance, DP/30 interview

2. Derek Cianfrance, Slashfilm.com interview

3. Derek Cianfrance, Making Of interview

4. Derek Cianfrance, DP/30 interview