“The idea at the time was from Fabrizio De Angelis, the producer. He called me at the time and said, “What do you think about The Bronx Warriors?” I said, “Great! Is it the next movie of Walter Hill?” “No, it’s your next movie!” I said, “Great, OK.”… The movie was inspired, for sure, of course, from Escape From New York. I watched that movie 1,000 times. And Mad Max. Mad Max for the cars, the costumes.”

Enzo G Castellari

“It’s not just westerns, not just war films – there’s a bunch of sub genres inside of those. And that’s what I like the most, are sub-genres, and then bouncing a bunch of those off of each other. And the thing is, I never want to play them straight, I always want to transcend them, I just want to use them as a jumping off point to do something else. But I don’t want them to be some pretentious, artistic, art film meditation on the genre. I want to go and do it my own way. So I want to give you the same pleasures but go to a different drummer.”

Quentin Tarantino

In his book The Story Of Film, Mark Cousins evokes both Richard Dawkins’ concept of memetics and EH Gombrich’s theory of ‘schema plus correction’ for art history to talk about the “grammar of film”, which, Cousins suggests, “grows and mutates”. Richard Dawkins first proposed the study of memetics in The Selfish Gene (1976) as a cultural parallel to genetics, where, instead of biological information, ideas are transmitted between humans, through imitation. Dawkins suggests that, as in the genetic process of evolution, for ideas/memes to survive, variation, replication and ‘fitness’ all must apply. However, Cousins, who finds Dawkins’ proposal inadequate, suggests that cinema doesn’t evolve in a standard sense – “Advancing, getting more complex, building on the past” – and that often older trends resurface, regaining popularity. He seems to suggest a certain potential circularity in cinematic trends that undermines any comparison to genetics, but perhaps this is misguided, given how young the art of filmmaking really is. Cousins goes on to suggest a twist on Gombrich’s approach, in order to find “a useful model for understanding the nature of filmic influence”, which he describes as ‘schema plus variation’. Like Gombrich, he believes that, “For an art form to evolve, original images can’t always be copied slavishly.” His focus, therefore, is on the films that “vary the schema”, break new ground and influence other films.

By definition, Cousins’ history has no room for second-generation films like 1990: I Guerrieri del Bronx (1990: The Bronx Warriors, Enzo G Castellari, 1982), but Dawkins’ proposal is particularly helpful when looking at the Rip-Off, an enterprise that, after all, is uniquely based on the replication and mutation of single, definable concepts. If cinematic properties, or aspects of them, can be considered memes (in the Dawkinsian sense, as opposed to the internet meme), then Mutant Hybrids can be considered experiments to repurpose these to create new units of culture. Therefore, the Mutant Hybrid Rip-Off is a film wherein recognisable elements of existing films are utilised to create a new one. Essentially, they are films that use other films to tell their stories. Mutant Hybrids are cinematic analogues for genetic modification and they tinker with the natural evolution of film in the manner of the experiments of the clichéd mad scientist.

Unfortunately for some, genetics is defined by survival-of-the-fittest rule and few would argue that Robo Vampire (Godfrey Ho, 1988) was ever destined to live a full and happy life, spreading its seed far and wide and begetting a rich lineage. Its infamous director enjoyed a long career taking Roger Corman’s legendarily economical production techniques to absurd lengths. Ho’s films are legendary for stitching together footage from completely unrelated films with his new, cheaply filmed footage, redubbing the dialogue and also stealing well-known music for his soundtracks. Robo Vampire not only attempts to co-opt the story and character of RoboCop (Paul Verhoeven, 1987), pitting him (see above) against strange, hopping vampires, but also stitches two seemingly unrelated films together in the process. By comparison, the non-Mutant Hybrid Star Wars is the Genghis Khan of the movie world, raping and pillaging its way across the globe, leaving an indelible mark on the landscape and stamping its DNA on the creative genes of filmmakers worldwide. It is, of course, arguable that Star Wars and its offspring may prove an evolutionary wrong-turn, but its longevity and far reaching influence have proved it ‘fit’ enough to survive in our time. The first two films of Lucas’ original trilogy have been preserved by the US Library of Congress as part of the National Film Registry – Robo Vampire and The Phantom Menace still pending.

Films classed as Rip-Offs are rarely credited with originality or influence and more often that not are considered creative dead-ends. It is arguable that many films in this category are the fairground oddities of the movie world, albeit more Freaks than The Elephant Man. Just as the popularity of the freak show aesthetic has become a niche concern, any box-office draw these movies may have enjoyed in their day has comparatively dwindled and they are effectively cordoned off in the ghetto of B-movie fetishists. However, they retain a unique appeal due to the many entertaining, bizarre and provocative elements they contain. Some of them had the potential to be the outliers but proved to be outcasts – more Johnny Eck than Professor X – instead and are genuine lost or underappreciated classics.

Cousins’ example, as exclusionary as it is, does help us to distinguish those from the likes of the Asylum’s generic (in the worst sense of the word) output. More often than not, the most interesting thing about the Asylum’s films is their covers, which promise the world and deliver ashes. The best of the Mutant Hybrids, in their virulent originality, challenge even the validity of the term “Rip-Off”, in a fashion not dissimilar to Michael Corleone’s attempts to take his family’s mob business legit. These are the movies that roam the generic no-man’s land, the muties that defy easy categorisation. In this they are the key to the intrinsic paradox of the Rip-Off – they are free to be whatever their filmmakers can possibly envision – and, of course, not all of these films and filmmakers rise successfully to that challenge – so long as they hit the bass notes of commerce and financial equilibrium. Some would argue this is the foundation of the whole B-movie culture – If it isn’t broke don’t break it; just give it a new paint job, and make sure there’s plenty of nudity and violence.

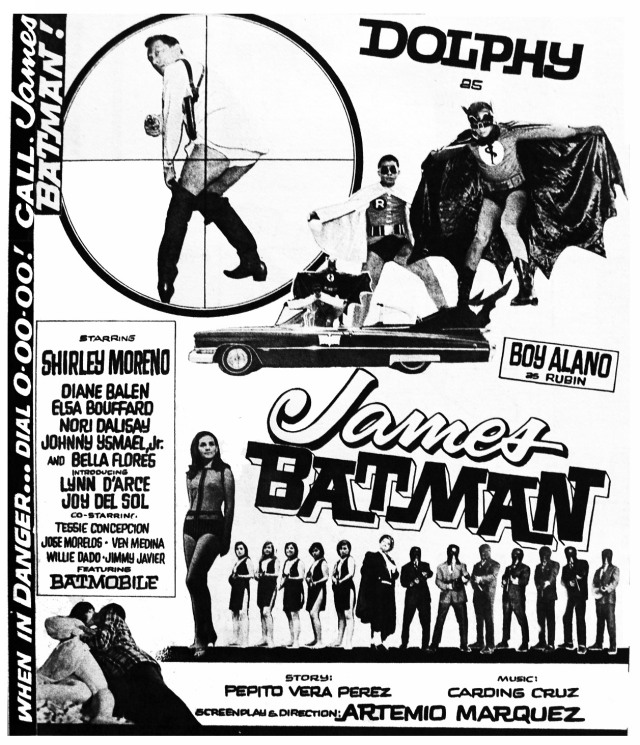

There are perhaps three delineable kinds of Mutant Hybrid Rip-Off – the more benign, Frankensteined kind that incorporate or bastardise footage from other films (see Turkish Remakesploitation of the late 1970s – mid 1980s, Hollywood Boulevard (Joe Dante, 1976), Ultra Warrior (Augusto Tamayo San Romån/Kevin Tent, 1990)), the half-breed kind that take two or more properties and marry them together (James Batman (Atemio Marquez, 1966), Emanuelle and the Last Cannibals (Joe D’Amato, 1977)) and the kind that combine discernable elements of other films to create entirely new, meta-textual monsters. In this latter category belong the likes of The Mighty Peking Man (Ho Meng-hau, 1977), the Kill Bill films (Quentin Tarantino, 2003/04) and The Ice Pirates (Stewart Raffill, 1984). Shaun of the Dead (Edgar Wright, 2004) could also be considered one of the more famous and recent Mutant Hybrid Rip-Offs, given that it consists of a broad pastiche of George A Romero’s zombie films meshed to a romantic comedy narrative.

Few would argue Shaun of the Dead doesn’t owe a huge debt to the films of George A Romero, but its narrative is almost entirely original. Its action arguably plays out in the same cinematic world as Romero’s films, obeying their famous rules and deliberately mirroring the global events related in the originals. But few would feel comfortable condemning it a Rip-Off, given that it wears its influences so clearly on its sleeves, and the plethora of “…Of The Dead” movies that exist even beyond Romero’s canon. However, it certainly is entirely reliant on extant films for its aesthetic and narrative tropes, and operates strictly within the aforementioned Romero Rules for his zombies saga. One horror antecedent that is more of a straight-up Mutant Hybrid is Emanuelle and the Last Cannibals (Joe D’Amato, 1977), which combines the character of Emanuelle (Laura Gemser), an unauthorised Italian knock-off of the Emmanuelle series (note the extra ‘m’) with the emerging cannibal film genre.

Films that repurpose footage from other films for comedic effect, the best example of which is probably Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid (Carl Reiner, 1982), can create entirely new cohesive narratives with an intriguing mixture of integration and juxtaposition. Reiner’s film noir parody is carefully built around several clips from famous films of the 1940s. These are perhaps better considered as examples of détournement than the Mutant Hybrid. There are also many examples of films that have been redubbed in part or détourned in their entirety chiefly for comedic effect, and so do not necessarily belong in this category. A Man Called…Rainbo (David Casci, 1990) and What’s Up, Tiger Lily? (Woody Allen, 1966) are among these. There is a long history of ‘official’ hybrids ranging from the Abbot And Costello Meet… series (1948-55) to the recent AVP: Alien Vs Predator (Paul WS Anderson, 2004). Films such as these undoubtedly share some of the ulterior motives of the Mutant Hybrid – the prospect of doubling a potential audience by combining two proven properties. However, the imagination and creativity they inspire in their makers and audience is inversely proportional to their cynicism. Interesting oddities like Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter (William Beaudine, 1966), the Wizards Of Mars (David L Hewitt, 1965) and even Forbidden Planet (Fred Wilcox, 1956), which take real life or literary characters or narratives and repurpose them are also not Movie Rip-Offs per se. Finally, films such as Delta Force Commando (Pierluigi Ciriaci, 1988), which ingeniously combines the titles of two successful films, are less often as overtly derivative of the content of those films as could be expected.

Roger Corman has a justified reputation as the King of the B’s (although he would argue semantics on the definition of B-movies) but with responsibility for almost 400 films and a reputation for thrift, it’s unsurprising that a few of his films recycled footage. His Edgar Allan Poe cycle (eight films, 1960-64) reused footage from the climax of the first, House Of Usher, several times over. Peter Bogdanovich’s Corman-produced Targets (1968) reused footage from The Terror (Roger Corman, 1963) in order to compliment and capitalise on two days work the star of latter, Boris Karloff, owed Corman. The footage was justified by casting Karloff as an aging movie star making a promotional appearance at a drive-in theatre where the action climaxes. A similar ruse was the basis for one of the definitive Frankensteined films, Hollywood Boulevard (Allan Arkush/Joe Dante, 1976). Co-director Joe Dante wrote a script based around a movie studio, allowing him and Arkush to deliver a film consisting of an absurd amount of disparate footage from Corman’s vaults. The result was more tongue-in-cheek rather grossly cynical.

Corman’s treatment of Nippon Chinbotsu (The Submersion of Japan, Shirô Moritani, 1973) a film he repurposed for the American market was arguably more so. Renaming it Tidal Wave, Corman ordered it recut and redubbed with new scenes shot starring Lorne Michaels as a UN representative in Japan. This approach to foreign films was not usual for Corman – he says it was “probably the most outrageous example of reediting a film for domestic release” – and his New World Pictures actually released many foreign and art house films untouched, opening them up to large, new audiences. The Slaughter (Michael Findlay, 1971), filmed in Argentina, was not treated as well when it was bought by producer Allan Shackleton, who tacked on scenes at the end supposedly depicting the crew of the film brutally murdering a young woman. Shackleton renamed it Snuff (1976) and promoted it as a genuine snuff film.

There are some great examples of the Mutant Hybrid that are unfortunately obscure to the point of lost. Andy Warhol’s Batman Dracula (1964) not only ‘homaged’ the Batman serials of the 1940s and the character of Dracula, but prefigured the camp style of the 1960s Batman TV series. There was also a sequence of Filipino Batman Rip-Offs in the 1960s, which started with Alyas Batman at Robin (Paquito Toledo, 1965) and included Batman Fights Dracula (Leody M Diaz, 1967) and, most intriguingly, James Batman (Atemio Marquez, 1966), a spoof Hybrid of James Bond and Batman, where the lead actor (comedian Rodolfo Vera Quizon Sr, AKA Dolphy) played both roles. Frustratingly, beyond a couple of YouTube clips, the films are particularly hard to track down.

The opening quote above, from Enzo G Castellari (delivered in an interview for Shameless’s DVD release of his Bronx Warrior Trilogy), suggests the ease with which the decision was made to rip off Walter Hill’s iconic New York gang fable The Warriors (1979), but it also tells us much more. Firstly, the project was, as is so often the case with Rip Offs, rooted in the shark-like instincts of a producer who had smelled blood in the water. Secondly, the director was more than just aware of the original work – he was a fan. And then, wonderfully, Castellari proudly declares the influence of the other key films that shaped the classic Mutant Hybrid Rip-Off, 1990: The Bronx Warriors.

From Walter Hill’s film, he took the authentic setting (although interiors were filmed in Rome, Castellari seamlessly integrated footage shot on location in New York), the colourful aesthetic of the various gangs (the bare-chested, leather waistcoated look of the Warriors themselves, the painted faces and general incongruity of the Baseball Furies) and the antagonism between the gangs in the midst of general lawlessness. From Escape From New York (John Carpenter, 1981), he took the general plot outline – a person of importance to the ‘outside’ world (the daughter of a scheming industrialist rather than Carpenter’s President) needs rescued from the lawless, post-apocalyptic Bronx. As Castellari’s proclamation suggests, the influence of Carpenter’s film permeates his own, from the nihilistic outlook of the anti-hero, Trash (Marco Di Gregerio, billed as Mark Gregory) to the authority figures monitoring the action. From Mad Max (George Miller, 1979), well, “the cars, the costumes” pretty much sums it up, although Miller, Carpenter and Castellari all tell their bleak, anti-heroic stories in similarly dystopic settings. Peckinpah-influenced slow motion set pieces, prevalent in Castellari’s ouevre, also appear in The Warriors, particularly when the Warriors fall foul of the Lizzies (“The chicks are packed!”).

So Castellari’s film is already notable for directly ripping off not just one but three movies. But the impressive and important thing about 1990: The Bronx Warriors is not that it steals so much from other movies, but that these elements are so well synthesised, reinterpreted and mixed with singular, original elements that the finished product demands to be judged on its own merits, even while it barely tries to conceal its various influences. The lone drummer practicing on the riverside as Trash and his biker gang arrive, Fred Williamson’s faux-noble, badass demise and Di Gregerio’s preening, effeminate machismo (which amps up Michael Beck’s performance as Swan in The Warriors to a homoerotic fever pitch) all contribute to the unique character of Castellari’s film. There were, of course, to be many post-apocalyptic, gangs roaming the wasteland films around this period (including the cycle of Italian films that 1990 is a part of), but Rip Offs are often the stepping-stone from unique, groundbreaking films to brand-new genres.

Many films quote or homage previous films, but some take the notion to the extreme. Jared Auner at Worldweirdcinema has pointed out the standard “cut and paste” approach of Bollywood to Hollywood output, where the narrative of one film can be embellished with elements of others to produce a new work. As Auner points out, Baadshah (Abbas-Mustan, 1999) broadly mimics Nick Of Time (John Badham, 1995) while incorporating elements of The Mask (Chuck Russell, 1994), Rush Hour (Brett Rather, 1998) and Mr Nice Guy (Sammo Hung, 1997).

Edgar Wright and, most famously, Quentin Tarantino (who has described Enzo G Castellari as “my maestro”), both use the visual and audio language of cinematic history as the raw material with which they stitch together their own paradoxically original work. Tarantino has said, “You could almost make an analogy that there is almost a hip hop equivalent to the way that this is sampled and that is sampled, but doing it in a cinematic way.” Although there are many examples in Tarantino’s oeuvre, the Kill Bill films probably stand as the strongest examples of his method, splicing broad generic elements of spaghetti western, Shaw Brothers-style kung fu films, anime, giallo and revenge films with specific filmic and cultural references (though Tarantino believes the extent of his use of allusion is exaggerated), all while producing work that is recognisably ‘Tarantinoesque’. That this term has not by now become redundant is a mark of his enduring talent and the wilfully blinkered vision of his detractors. Rather than go to film school, as he has been quoted, “I went to films”. The director himself makes no qualitative distinction between high and low-brow cinema while he is generally respected for his encyclopaedic knowledge of cinema history. Only in the very earliest days in his career were questions of his cinematic ‘theft’ not met with a general awareness and acceptance of the fact that Tarantino makes no effort to conceal his sources and in fact at every turn, perhaps more than any other filmmaker, encourages his audience to seek out the very films that he is ‘stealing’ from. As a sidenote, although it has not (as yet) featured in any of his films, Tarantino re-released The Mighty Peking Man (Ho Meng Hau, 1976), a Mutant Hybrid combining a King Kong-alike with a female Tarzan analogue.

So Tarantino has made a successful career creating films that freely make use of cinematic references to create original work. Many of his films can be said to rely to a greater or lesser degree on the audience’s awareness of the providence of the cinematic ‘quotes’. These can enhance the enjoyment of the films in the same sense as the first wave of modernist authors made oblique use of classical and other references to simultaneously enrich their work and also answer the widening of the general readership to include the uneducated classes. So there is a sense of exclusivity that can be read into the enjoyment of these films on that level – that you may feel flattered and included in a privileged club, the members of which can recognise and appreciate the references being made. However, in the context of popular cinema, this exclusivity is countered by the visceral, arguably even base, enjoyment of the films in question. Kill Bill is, first and foremost, a ‘roaring rampage of revenge’ and never makes any claims otherwise. As Tarantino has said,

“If you understand the context in which I’m coming from and the genres that I’m evoking and the moods and the feelings of them, well then, that’s great, now you can appreciate it in that way and that’s all good. And if you haven’t, then it’s all brand new to you and you can look at in a completely different way and now it’s got to work in a whole different way for you because you don’t understand the genre, I have to take you there myself.”

The best Mutant Hybrids display their respect and affection for the films they rip off by creating new, equivalent work that arguably can surpass the source material. They share a passion for the original work with the makers of Fan Films and similarly speak in the language of these movies. The filmmakers honour their influences by matching their creativity, inventiveness and entertainment value. Just as mankind has begun tinkering with genetic modification to interfere with natural genetic procedures, those that keep these often absurd and brilliant films alive are playing with the ‘natural selection’ of canonical film academia and even popular “all time greatest” polls to celebrate what is really possible if you throw aside conventional notions of quality, originality and legality. As the average human lifespan increases, so to does the shelf life of films previously too perverse to live.

So what is the future of the Mutant Hybrid? Tech-savvy Machinima filmmakers have already shown their willingness to use the medium of computer game engines to create narrative cinema that utilises user-controllable elements in artificial environments. Originating with short animations created with gameplay recordings of Quake (see Diary Of A Camper (Matthew Van Sickler, 1996)), Machinima has reached maturity with The Trashmaster (Mathieu Weschler, 2010), a full-length feature created solely in the artificial world of Grand Theft Auto IV. A recent (so far unsubstantiated) rumour had George Lucas gathering the likeness rights to dead actors in order to reanimate them digitally, perhaps with the aid of motion capture in James Cameron’s The Volume. In the future, modern actors (or even civilians) could ‘puppet’ long gone Hollywood icons, inserting them into modern narratives – inserting them anywhere. Sooner or later, these avatars could be as widely available and easily manipulable as any computer game character. From here, disregarding momentarily humanity’s inevitable slide into a Matrix world of digital reverie and/or star-fucking porn, these familiar skins could perform in any number of ways in any number of heretofore-impossible narratives. Like every other medium, when exposed to the catalyst/accelerant of the lawless internet, these skins and the facility to animate them will belong to everyone in the world with a laptop and the will to use them. Greedo shot first? Fuck you – it was Jar Jar on the grassy knoll beyond the cantina. Would Tom Selleck have made a superior Indiana Jones? Wonder no more. No need to wait in vain for Bronx Warriors 3: Escape From The Earth, or track down the long-lost Marco Di Gregerio to reprise Trash. Nicolas Cage will play Trash with Di Gregerio’s face. Elle Fanning will play Nicolas Cage. Nobody will remember the lessons we should have learned from Aliens Vs Predator while Alien Vs Glee distracts us momentarily from screen to flickering screen as we direct Natalie Portman and Jack Lemmon in The Apartment 2: After The Fall Of New York. In the meantime, the search for James Batman continues.

www.worldweirdcinema.blogspot.com

www.tarantino.info/wiki/index.php/Kill_Bill_References_Guide