“The public has been hampered in the knowledge of Scientology by the fact that so far as I can establish, on every occasion that the organisation has been named by a newspaper, that newspaper has been served with a writ of libel.”

Peter Hordern MP, Parliamentary debate, 6th March, 19671

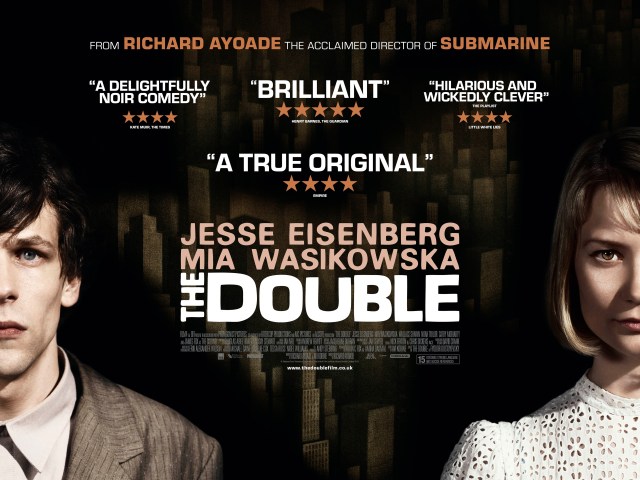

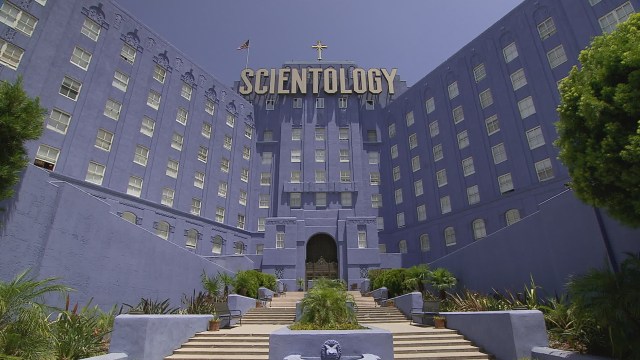

Alex Gibney’s adaptation of Jeffrey Wright’s book, Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood & The Prison of Belief, on the rise of the most notorious of new religions, reaches us – by the skin of its teeth, seemingly – through a predictable fugue of potential lawsuits. Indeed, the Church of Scientology’s reliably dogged insistence on making the film’s journey to GFT or any other screens as difficult as possible is probably better publicity than a shipping container full of dinosaurs abandoned in Waterloo Station. If anyone is in any doubt about the relevance of Gibney’s documentary to British audiences, they need only refer to the vehemence of the Church’s opposition.

This is behaviour the general public has come to expect of the Church and while it certainly evokes the Streisand Effect more than a little bit, it is also worryingly effective. In fact, Wright’s book, widely credited with doing its level best to give L Ron Hubbard and Scientology a fair shake, still hasn’t been published in the UK. That’s because historically in the UK (well, England and Wales) the burden of proof in defamation cases has rested upon the defendant. That means UK publishers have been especially vulnerable when faced with the aggression, persistence and sheer means of the deep-pocketed religion.

Likewise, while the 2013 Defamation Act amended UK law so that plaintiffs must demonstrate “serious harm” has been done to them, there are currently no confirmed plans to broadcast Gibney’s film, produced and broadcast by HBO in the US, in the UK. Reportedly that’s because Sky Atlantic, who control the UK rights, can’t differentiate its signal between regions, meaning a UK broadcast would necessarily include Northern Ireland, where the 2013 Act has not been made law (nor has it in Scotland, though reporting on the issue has mostly focused on Ireland, where the DUP have been vocal in their opposition to reform).

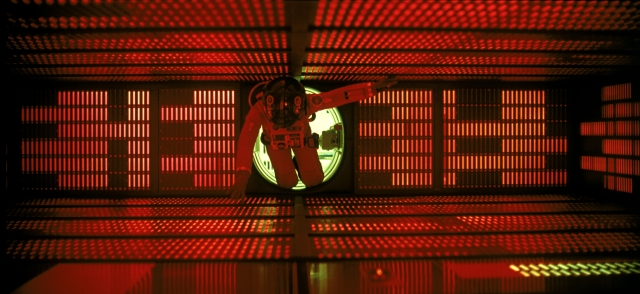

Scientology has almost always had a fractious, defensive relationship with the media. Almost, but not quite, as evidenced by some of the most remarkable footage in Going Clear, drawn from two episodes of Granada’s World In Action series – ‘Scientology For Sale’ (August 1967) and ‘The Shrinking World of L Ron Hubbard’ (August 1968) – as well as “off-the-record”2 outtakes from the second programme. The casual access allowed to the church’s founder, L Ron Hubbard, would not be repeated.

The footage also reminds us that although modern fascination with Scientology, morbid or otherwise, is mostly focused on the distant antics of Tom Cruise, or folded into the “only in America” compartment of our collective unconscious, the Church actually has a long history in Britain, as demonstrated in the opening quote above, from a Parliamentary discussion on Scientology in 1967.

In Britain too, the following year, the magazine Queen (later Harper’s & Queen, now Harper’s Bazaar) published ‘The Scandal of Scientology’, one of the first exposés of the church. The author, American journalist Paulette Cooper, soon expanded her article into a book of the same name (just as Wright developed his controversial New Yorker profile of director Paul Haggis into Going Clear) and soon became the focus of successive covert campaigns (Operations Daniel, Dynamite and Freakout) aimed at discrediting her. She explains:

“I ended up falsely arrested and facing 15 years in jail, had 19 lawsuits filed against me all over the world by Scientology, was the almost victim of a near murder, was the subject of five disgusting anonymous smear letters sent to my family and neighbors about me, and endured constant and continual harassment for almost 15 years.”3

Scientology, as I’ve suggested, were never going to take Going Clear lying down. Earlier this year, they took out a full-page advert in the New York Times, criticizing both Gibney and HBO executive Sheila Nevins, comparing the documentary to the controversial, discredited Rolling Stone report on campus rape at the University of Virginia with an enormous headline reading, “Is Alex Gibney’s Upcoming HBO ‘Documentary’ a Rolling Stone/UVA Redux?”

While Gibney countered that a full-page ad is the “chosen device of a business protecting market share, not [a] church protecting belief,”4 it’s still ironic (or apposite, depending on your mood) that Scientology’s legal threat has reportedly “curtailed”, marketing plans for the film’s UK screenings, while the distributors and exhibitors involved asked not to be named in recent reporting.5 Nevins, meanwhile, is unrepentant. “[Documentaries] don’t get full-page ads,” she said recently, “and when they do, they do really well…Scientology did their own commercial for us.”6

Scientology have also set up propaganda (or counterpropaganda, depending on your mood) websites and invested heavily in promoting them. Google “Alex Gibney” and you’ll find the top hit for the Oscar-winning filmmaker is a sponsored link to a Scientology website dedicated to attacking him and his collaborators. Each merits a dedicated page and bespoke video dismantling their characters, undermining their testimony but not directly countering their accusations. Gibney asserts in return that, “a careful investigation of the church’s claims will reveal that most of the misdeeds by critics… were committed on behalf of the Church of Scientology… These people are now repenting and the Church of Scientology wants to punish them.”7

The version of Going Clear we’re getting has reportedly been edited from the original US broadcast, although there are suggestions this may extend simply to on-screen legal disclaimers. Despite that, there are suggestions the Church are even now trying to block Going Clear’s cinema release entirely, meaning I might be wasting my time writing this. On the other hand, perhaps I’ll avoid the fate of the US film reviewers who received the following email:

“The above article concerning Going Clear, Alex Gibney’s film, was posted without contacting the Church for comment. As a result, your article reflects the film which is filled with bald faced lies. I ask that you include a statement from the Church in your article. There is another side to the story which has to be told. Do not be the mouthpiece for Alex Gibney’s propaganda.”8

Sean Welsh, June 2015

This article was originally commissioned as a programme note by GFT.

Footnotes

1. Hansard, 6th March, 1967

2. Alex Gibney, ‘Alex Gibney on Going Clear’s Archival Scientology Footage, Using Drones, and Why More People Need to Speak Out Against the Church’ by John Horn

3. Paulette Cooper, ‘The Scandal of The Scandal of Scientology’

4. Alex Gibney, Twitter, 16th January, 2015

5. ‘Scientology doc to get UK release despite pressure’ by Andreas Wiseman

6. Sheila Nevins, ‘Here’s the moment HBO knew its Scientology doc ‘Going Clear’ would be a huge hit’ by Jason Guerrasio

7. Alex Gibney, ‘Church of Scientology targets film critics over Going Clear documentary’ by Ben Beaumont-Thomas

8. Ibid.