“..its origin and purpose still a total mystery.”

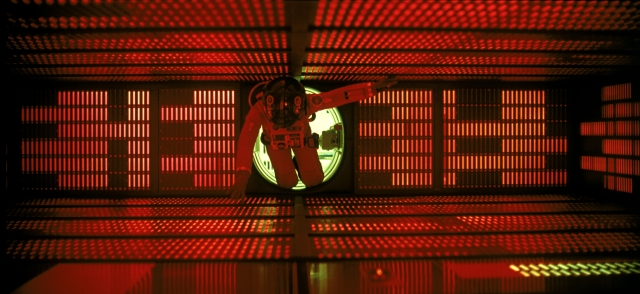

Dr Heywood R Floyd (William Sylvester) in 2001: A Space Odyssey1

“Worth going to see? I can well believe it / Worth seeing? Mneh!”

WH Auden, Moon Landing2

In 1968, when most people alive today – to steal Arthur C Clarke’s phrase – had not even been born, Stanley Kubrick made his acknowledged masterpiece. Experiencing it in 2014, perhaps for the first time and 42 years since the most recent manned Moon landing, it’s easy to forget that 2001: A Space Odyssey was made before Man had first walked on the Moon – before we as a species had even seen our planet from any real remove. Our understanding of 2001, and more particularly our experience of it, has inevitably changed in the 46 years since its debut, even as the film itself shaped the future unfolding before it.

2001 remains a definingly Kubrickian mixture of neurotic specificity and compelling opacity, encouraging both close reading and wild-ranging interpretation. The film is certainly aged, sometimes by elements originally and paradoxically prescient. For example, the corporatization of space travel (ref Virgin Galactic) is predicted, although time would excuse the prominently featured Pan Am and Bell from any real race to the stars. Later, 1992 came and went without HAL becoming operational*, though IBM did lose $5 billion, ‘more than any US company has ever lost in a single year.’3 2001 itself passed by with only an affectionate nod in the naming of the 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft to mark it. And even 2010 was less The Year We Made Contact4 than the year we made Little Fockers.

2001 is also ageless, owing almost entirely to Kubrick’s stated aim to make it “basically a visual, nonverbal experience,” akin to music in its ability “to cut directly through to areas of emotional comprehension.”5 In essence, Kubrick meant that audiences should be active rather than passive participants in the experience of his film – that 2001 should be happening to you as much it’s happening to Dr David Bowman. When Christopher Nolan recently referred to his Interstellar (2014) as an “experiential”6 film – confusing a legion of sub editors and readers who decided he must mean ‘experimental’ – he was consciously evoking the intended experience of watching 2001.*

On the occasion of the Apollo 11 mission in 1969, WH Auden wrote a derisory poem, for publication in The New Yorker. In Moon Landing, he seems to dismiss the entire endeavour as a classic example of risible machismo (“an adventure / it would not have occurred to women / to think worth while”7). Indeed, a common analysis of 2001 bears that perspective out. As Camille Paglia opined, “From the first second that the first weapon is found – the weapon that is the tool, OK, that is the work of art – all these things were forced forward by male testosterone, and by a kind of homicidal impulse to create and to kill.”8 It’s the apes’ discovery of weaponry and violence that propels their evolution towards Man and, by extension, Man’s drive towards exploring (read militarizing) space.

Referring to Clarke’s novel of 2001 (created in parallel with the film and the product of close collaboration with Kubrick) will not prove anyone’s interpretation of the film – they are entirely distinct entities and the film should properly be considered a self-contained experience – but it often proves instructive. In the novel, it’s heavily implied that without the intervention of the monolith, the antecedents of Man would have perished, so unsuited were they otherwise to the harsh environment in which they lived. Conversely, while Clarke is confident that the famous, four-million-year spanning match cut from a thrown bone lands on “an orbiting space bomb, a weapon in space.”9, it’s not actually made explicit in the film, and deliberately so. Whether he intended to avoid comparison with his own Dr Strangelove (1964), or to fend against obsolescence in the face of impending treaties forfending the militarization of space, Kubrick’s overriding tendency was to discourage such a reductive interpretation – or at least to refuse its singularity.

On the other hand, Kubrick was never reluctant to ‘explain’ 2001, at least in terms of what is depicted on screen. In fact, he was positively forthcoming as far back as 1969:

“You begin with an artifact left on Earth four million years ago by extraterrestrial explorers who observed the behaviour of the man-apes of the time and decided to influence their evolutionary progression. Then you have a second artifact buried deep on the lunar surface and programmed to signal word of man’s first baby steps into the universe – a kind of cosmic burglar alarm. And finally there’s a third artifact placed in orbit around Jupiter and waiting for the time when man has reached the outer rim of his own solar system.

“When the surviving astronaut, Bowman, ultimately reaches Jupiter, this artifact sweeps him into a force field or star gate that hurls him on a journey through inner and outer space and finally transports him to another part of the galaxy, where he’s placed in a human zoo approximating a hospital terrestrial environment drawn out of his own dreams and imagination. In a timeless state, his life passes from middle age to senescence to death. He is reborn, an enhanced being, a star child, an angel, a superman, if you like, and returns to Earth prepared for the next leap forward of man’s evolutionary destiny.”10

That’s 2001, according to Kubrick, “on the film’s simplest level.”11 But what does it all mean? To one extent or another, 2001 is what you make of it. “Stanley wanted to create a myth,”12 explained Clarke, and both were eager for audiences to form their own philosophical interpretations. What some more recent filmmakers – *cough* Nolan *cough* – often miss is that the pursuit of science is much more often about posing questions than providing answers. Likewise, the cinematic experiences those filmmakers claim to aspire to should challenge us more than they comfort us. As Terry Gilliam once said, “The Kubricks of this world…make you go home and think about it.”13

Sean Welsh, 2014

This article was originally commissioned as a programme note by GFT.

* Early in Nolan’s film, Matthew McConaughey’s Cooper is aghast at a school teacher’s blithe assertion that the 1969 moon landing was faked – merely a ploy, she maintains (though an ingenious one, she grants) to bankrupt the Soviet Union. Kubrick, of course, has long been a key figure for conspiracy theorists convinced he was enlisted to fake the 1969 Moon landing, a belief stoked by determinedly ingenuous viewers of William Karel’s mockumentary Opération Lune (2002).

Footnotes

1. “Except for a single, very powerful radio emission aimed at Jupiter, the 4-million-year-old black monolith has remained completely inert…”

2. WH Auden, ‘Moon Landing’, New Yorker, 6th September, 1969 p 38

3. John Burgess, ‘IBM’s $5 Billion Loss Highest in American Corporate History’ in The Tech, 20th January 1993

4. 2010: The Year We Make Contact (Dir. Peter Hyams, 1984) was the Clarke-approved, Kubrick-uninvolved sequel.

5. Stanley Kubrick (1969), ‘An Interview with Stanley Kubrick’, interview with Joseph Gelmis in The Film Director as Superstar (Garden City, New York: Doubleday and Company, 1970)

6. Christopher Nolan (2014), ‘Christopher Nolan Breaks Silence on ‘Interstellar’ Sound’, The Hollywood Reporter, 15th November, 2014

7. Auden, ibid. 1

8. Camille Paglia, 2001: The Making Of A Myth (Dir. Paul Joyce, 2001)

9. Arthur C Clarke, 2001: The Making Of A Myth (Dir. Paul Joyce, 2001)

10. Kubrick, ibid. 5

11. Kubrick, ibid. 5

12. Clarke, ibid. 9

13. Terry Gilliam, TCM interview, ‘Terry Gilliam criticizes Spielberg and Schindler’s List’

Really enjoying these well researched insights. Need to see these films again

LikeLike